All too soon the week that had stretched before us shrank to the last day; there were final dusty gatherings by the water tap and at our sanctuary – a little café we discovered on the banks of the Torrens. There would be no more shuffling around of green plastic chairs, trying to work out which way the sun would move, and no more casual chats, sharing opinions about the latest books.

Thornton McCamish has written a book about the Australian writer Alan Moorehead – a writer I remember well from my late childhood and adolescence – I received The White Nile as a school prize. Thornton’s book, Our Man Elsewhere: In Search of Alan Moorehead is described as a ‘must read’ for anyone interested in Australian literary history. I’m sure I never met Alan Moorehead, or heard him speak, but it sounds as though he was one of those mid 20th Century Australian gentlemen who believed you had to sound plummy English. He was first known as a war correspondent (World War II). Thornton describes him as ‘an eye level writer’. Moorehead went to Europe in 1936 (those days when to make anything of yourself it was believed you must ‘go abroad’) and of course it was an ideal time for a journalist to be there: the British abdication, the Berlin Olympics, the Spanish Civil War. When World War II started, Moorehead was there. He wrote in a morale-raising kind of way, leaving out the blood and gore (as one did in those days).

Thornton said he finds fascinating ‘the time machine of the prose’ – it gives a lived experience of the past. To give the right effect, Moorehead wasn’t always firm with the facts, for example, he described tulips at a battle in Holland during a season when there couldn’t have possibly been tulips there. Thornton sums him up as a great travel writer. There was too much of him in his books for him to be a great fiction writer, but he was one of the first Australians to draw attention to the importance of conservation.

‘Homegrown’ was a session about the radicalisationof young Muslims. The session started with discussion about citizenship – how you can be summed up by how you look. Kamila Shamsie described how at her citizenship ceremony in London, holding the union jack, she felt ‘both the betrayer and the betrayed’. She had seen photographs of the union jack representing ‘empire’ in her birth country Pakistan, when it was still part of India and still part of the British Empire. She wanted British citizenship mainly so that she could travel with ease. She suggested that maybe ‘identity’ is what other people see you as being.

Kamila made the interesting suggestion that if you have grown up with a faith you may be more likely to reject ISIS, which appeals to young people who need something to follow – you are more easily brainwashed, she said, if you have grown up without religion. She said that when some young ISIS joiners were arrested, they were carrying copies of Islam for Dummies.

Laleh Khadivi reminded us that the young women who are radicalised have an even more difficult time than the young men, yet they are often making a ‘teenage mistake’ that they will never be able to turn away from.

Robert Wainwright has written a biography of Miss Muriel Matters, an Adelaide woman born in 1877, who became a famous suffragist. Her life was incredibly full: goat lady, elocutionist, educator and a leader of the suffragist movement in London. She travelled around in a caravan pulled by a horse called Asquith – after the prime minister – and later, used a dirigible to drop leaflets on the day the king opened parliament, at a time when most people hadn’t ever seen an aeroplane.

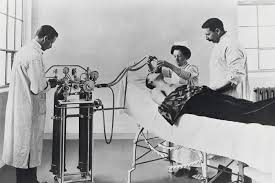

Kate Cole-Adams has written a fascinating book on anaesthesia – she spent 14 years working on it (although wrote other books during that time). Anaesthesia is described as an ‘unexplored story’ – and certainly it is unusual for a non-scientist to write about this subject. Kate cited researchers who say that anaesthesia is ‘more an art than science’. It is ‘getting rid of consciousness’ and consciousness is subjective. It seems that hypnosis can be beneficial – describing what we know of how anaesthesia works, Kate outlined three stages of conventional anaesthesia used today: 1. Hypnotic (you can learn things when under anaesthesia) 2. A strong pain killer 3. Muscle relaxants that paralyse (so even if you ‘wake up’, there’s no way you can do anything or communicate).

One point stressed by Kate is that anaesthesia is different for everyone.

To her amazement, when working on this book, Kate discovered that her grandfather had worked on a book: Mechanics of Consciousness from 1942 – 1950. He died before he could finish it.

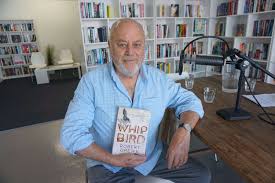

Understanding birds is a better way of understanding ourselves – this seems very likely after hearing Jim Robbins discuss his book The Wonder of Birds. Once again, Jim is not a scientist, indeed he suggested that science might be a barrier to understanding the ‘mystical language’ of birds. However, scientists can learn a lot from studying the brains of birds.(The derogatory term ‘bird brain’ is clearly inaccurate!) For example, canaries can grow new neurons to a far greater degree than humans are known to. If we studied this more, we might find a cure for Parkinson’s. I wasn’t so surprised to find that there is Machiavellian politics in the society of Ravens. Apparently crows hold funerals: do they have a soul? It is also interesting that birds may be able to see magnetic lines. Throughout the talk I thought about how humans have always wanted to fly – we often fly in our dreams – we create entities such as angels and fairies. It is an area of great fascination.

The final session I attended was inspirational. I have written about it elsewhere: Eddie Ayres, discussing his latest book, Danger Music. https://jenniferbryce.net/2018/03/09/eddie-ayres-danger-music/